Chapter 7: Religious Wars

By 1560, Europe was divided by religion as it had never been before. Protestantism was now a permanent feature of the landscape of beliefs and even the most optimistic Catholics had to abandon hopes that they could win many Protestants back over to the Roman Church through propaganda and evangelism. A patchwork of peace treaties across most of Europe had established the principle of princes determining the acceptable religion within their respective territories, but those treaties in no way represented something recognizable today as “tolerance” – in fact, all sides believed they had exclusive access to spiritual truth. Simply put, the very notion of tolerance, of “live and let live,” was almost nonexistent in early-modern Europe. Exceptions did exist, especially in the Holy Roman Empire, but beliefs clearly hardened over the course of the sixteenth century: what tolerance had existed in the early decades of the Reformation era tended to fade away.

This was not just about Catholic intolerance. While the Catholic Inquisition is an iconic institution in the history of persecution, most Protestants were equally hostile to Catholics. This was especially true among Huguenots in France, who aggressively proselytized and who imposed harsh social and, if they could, legal controls of behavior in their areas of influence, which included various towns in southern France, not just Switzerland. In addition, while actual wars between Protestant sects were rare (the English Civil War of the sixteenth century being something of an exception), different Protestant groups usually detested one another.

Why was religion so divisive? It was more than just incompatible belief-systems, with some of the reasons being very specific to the early modern period. First, religion was “owned” by princes. A given territory’s religion was deeply connected to the faith of its leader. Princes often held some authority in church lands, and priests had always served as important royal officials. There were also numerous ecclesiastical territories, especially in the Holy Roman Empire, that were wholly controlled by “princes of the church.” Likewise, only states had the resources to reform whole institutions, replacing seminaries, universities, libraries, and so on with new material in the case of Protestant states. This necessitated an even closer relationship between church and state. In turn, an individual’s religious confession was concomitant with loyalty or disloyalty to her prince – someone following a rival branch of Christianity was, from the perspective of a ruler, not just a religious dissenter, but a political rebel.

At the same time, over the course of the sixteenth century, specific, hardened doctrines of belief were nailed down by the competing confessions. The Lutherans published a specific creed defining Lutheran beliefs known as the Augsburg Confession in 1530, and the Catholic Council of Trent in the following decades defined exactly what Catholic doctrine consisted of. There was thus a hardening of beliefs as ambiguities and points of common agreement were eliminated.

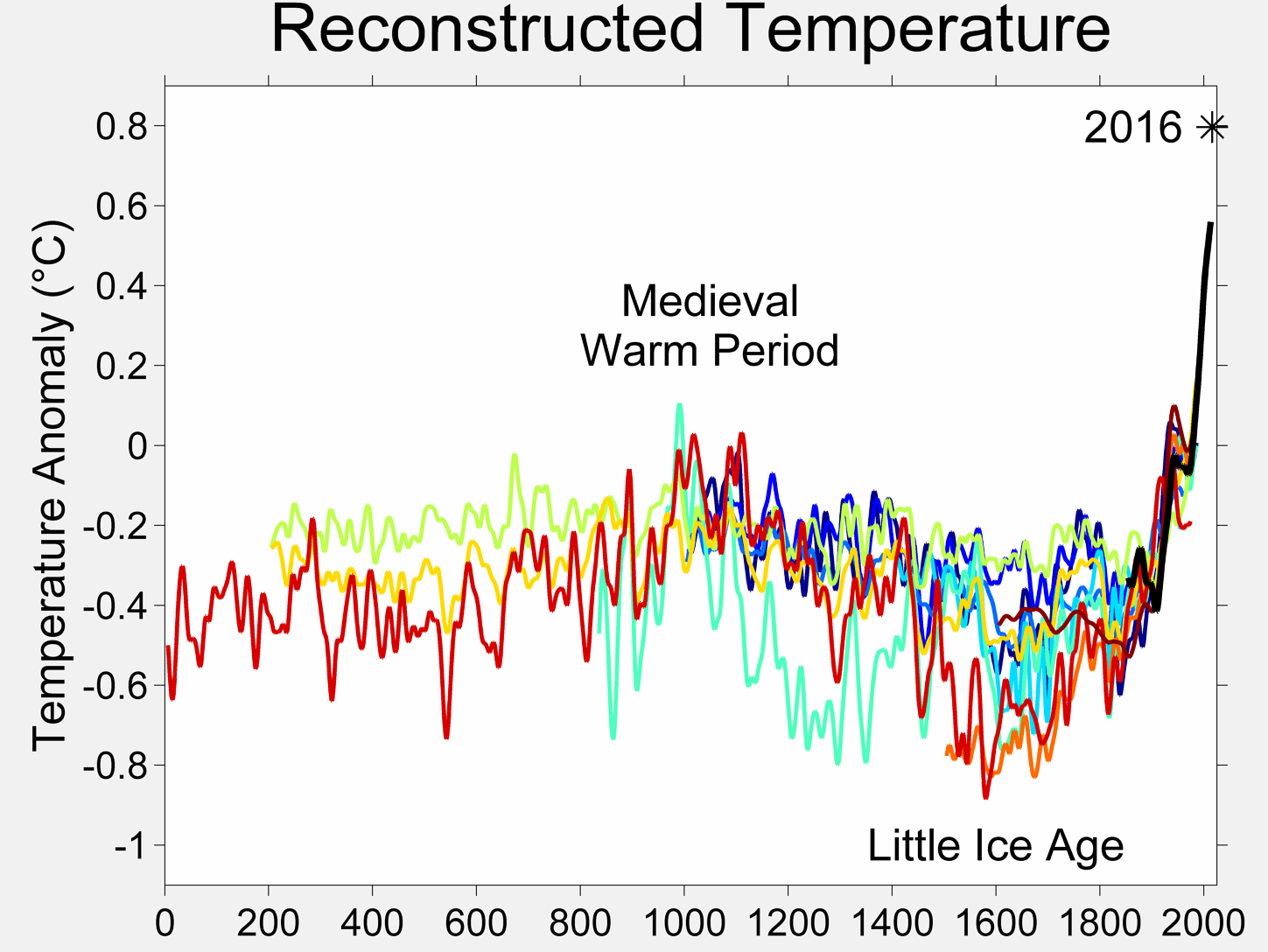

The Little Ice Age

Religion was thus more than sufficient as a cause of conflict in Europe in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. As it happens, however, there was another major cause of conflict, one that lent to the savagery of many of the religious wars of the period: the Little Ice Age. A naturally occurring fluctuation in earth’s climate saw the average temperature drop by a few degrees during the period, enhancing the frequency and severity of bad harvests. In the Northern Hemisphere, that change began in the fourteenth century but became dramatically more pronounced between 1570 and the early 1700s, with the single most severe period lasting from approximately 1600 until 1640, precisely when the most destructive religious war of all raged in Europe, the Thirty Years’ War that devastated the Holy Roman Empire.

Lower temperatures meant that crop yields were lower, outright crop failures more common, and famines more frequent. In societies that were completely dependent on agriculture for their very survival, these conditions ensured that social and political stability was severely undermined. To cite just one example, the price of grain increased by 630% in England over the course of the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, driving peasants on the edge of subsistence to even greater desperation. Indeed, historians have now demonstrated that not just Europe, but major states across the world from Ming China, to the Ottoman Empire, to European colonial regimes in the Americas all suffered civil wars, invasions, or religious conflicts at this time, and that climate was a major causal factor. Historians now refer to a “general crisis of the seventeenth century” in addressing this phenomenon.

Thus, religious conflict overlapped with economic crisis, with the latter making the former even more desperate and bloody. The results are reflected in some simple statistics: from 1500 to 1700, some part of Europe was at war 90% of the time. There were only four years of peace in the entire seventeenth century. The single most powerful dynasty, the Habsburgs, were at war two-thirds of the time during this period.

The French Wars of Religion

Against this backdrop of crisis, the first major religious wars of the period were in France. France was, next to Spain, one of the most powerful kingdoms in Europe. It was the most populous and had large armies. It had a dynamic economy and significant towns and cities. It also had a very weak monarchy under the ruling Valois dynasty, who were kept in check by the powerful nobility. The Valois kings were often no more powerful than their most powerful noblemen, some of the latter of whom had armies as large as that of the king himself, and many Valois kings had little skill for practical politics. For example, the Valois king Henry II ignored affairs of state in favor of hunting and was killed in a tournament (during a joust, a splinter from a broken lance flew in through the eye-slit of his helmet, impaling his eye – he died two weeks later from the subsequent infection), and other members of the dynasty were little more effective.

France was divided between two major factions, led by the fanatically Catholic Guise family and the Huguenot Bourbon family. The former were advised by the Jesuits and supported by the king of Spain, while the latter represented the growing numbers of economically dynamic Huguenots concentrated in the south (they were especially numerous in Navarre, a small independent kingdom between France and Spain that was soon embroiled in the war). As of 1560 fully 10% of the people of France were Huguenots, many of whom represented its dynamic middle class: merchants, lawyers, and prosperous townsfolk. In addition, between one-third and one-half of the lower nobility were Huguenots, so the Huguenots as a group were more powerful than their numbers might initially indicate. Fearing the power of the Huguenots and detesting their faith, the Guises created the Catholic League, an armed militia of Catholics that included armed monks, townsfolk, and soldiers. In 1562 a Guise nobleman sponsored a massacre of Huguenots that sparked decades of war.

From 1562 to 1572 there was on-again, off-again fighting between the Catholic League and Huguenot forces. The French king, Charles X, was a child when the fighting started and the state was thus run by his mother, Catherine de Medici, who tended to vacillate between supporting her fellow Catholics and supporting Protestants who were the enemies of Spain, France’s rival to the south. Despite their own professed Catholicism, neither Charles nor Catherine were fanatical in their religious outlook, much to the frustration of the nobles of the Catholic League.

Hoping to end the conflict, Charles and Catherine invited the Huguenot Prince Henry of Navarre, leader of the Protestant forces, to Paris in 1572 to marry Charles’ sister Margaret. Henry arrived in Paris with some 2,000 Huguenot followers, all of whom had agreed to arrive unarmed. The Duke of Guise led a conspiracy, however, to convince the king that only the death of Henry and his followers would truly end the threat of religious division, and with the king’s approval Catholic forces launched a massacre on St. Bartholomew’s Day, August 24, in which more than 2,000 Protestants were killed. That day, the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre, would live in infamy in French history as a stark example of religiously-fueled hatred.

The events in Paris, in turn, sparked massacres all over the country with at least 20,000 more deaths (supposedly, the pope was so pleased with the news that he gave 100 gold coins to the messenger who brought it to him). The one important person who survived was the leader of the Huguenot cause, Henry of Navarre, who half-heartedly “converted” to Catholicism to ensure his safety but then escaped to the south and rallied the Huguenot resistance. Charles died in 1574 of an illness, leaving his younger brother Henry as the last male member of his family line available for the throne. After a lull in the fighting, the war resumed in 1576.

In the years that followed, the French Wars of Religion turned into a three-way civil war pitting the Catholic League against the legitimate king of France (both sides were Catholic, but as focused on destroying each other as they were fighting Huguenots) with the Huguenots fighting both in turn. There was almost a macabre humor to the fact that the leaders of the three factions were all named Henry – King Henry III of Valois, Prince Henry IV of Navarre, and the leader of the Catholic League, Henry, Duke of Guise. Further assassinations followed, including those of both the Duke of Guise and the King. The only heir to the throne was Henry of Navarre himself, since he had married into the royal family, so after a climactic battle in 1594 he was declared Henry IV of France. He realized that the country would never accept a Huguenot king, so he famously concluded that “Paris is worth a mass” and converted to Catholicism on the spot.

Henry IV went on to become popular among both Catholics and Protestants for his competence, wit, and pragmatism. In 1598 he issued the Edict of Nantes that officially propagated toleration to the Huguenots, allowing them to build a parallel state within France with walled towns, armies, and an official Huguenots church, but banning them from Paris and participation in the royal government. He was eventually assassinated (after eighteen previous attempts) in 1610 by a Catholic fanatic, but by his death the pragmatic necessity of tolerance was accepted even by most French Catholics. Ultimately, the “solution” to the French Wars of Religion ended up being political unity instead of religious unity, a conclusion reached out of pure pragmatism rather than any kind of heartfelt toleration of difference.

Spain and the Netherlands

Following Henry IV’s victory, the royal line of the Bourbons would rule France until the French Revolution that began in 1789. The Bourbons’ greatest rivals for most of that period were the Habsburg royal line, who possessed the Austrian Empire, were the nominal heads of the Holy Roman Empire, and by the sixteenth century had control of Spain and its enormous colonial empire as well.

The Spanish king in the mid-sixteenth century was Philip II (r. 1556 – 1598), son of the former Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. Philip regarded his place in Europe, and history, as being the most staunch defender of Catholicism possible. This translated to harsh, even tyrannical, suspicion and persecution of not only non-Catholics, but those Catholics suspected of harboring secret non-Catholic beliefs. He viciously persecuted the Moriscos, the converted descendants of Spanish Muslims, and forced them to turn their children over to Catholic schools for education. He also held the Conversos, converted descendants of Spanish Jews, as suspect of secretly continuing to practice Judaism, with the Spanish Inquisition frequently trying Conversos on suspicion of heresy.

Philip was able to exercise a great deal of control over Spanish society. He had much more trouble, however, in imposing similar control and religious unity in his foreign possessions, most importantly the Netherlands, a collection of territories in northern Europe that he had inherited from his various royal ancestors. The Netherlands was an amalgam of seventeen provinces with a diverse society and religious denominations, all held in a delicate balance. It was also rich, boasting significant overseas and European commercial interests, all led by a dynamic merchant class. In 1566, Spanish interference in Dutch affairs led to Calvinist attacks on Catholic churches, which in turn led Philip to send troops and the Inquisition to impose harsher control. The most notorious person in this effort was the Spanish Duke of Alba, who sat at the head of a military court called the Council of Troubles, but known to the Dutch as the Council of Blood. Alba executed those even suspected of being Protestants, which accomplished little more than rallying Dutch resistance.

A Dutch Prince, William the Silent (1533 – 1584), led counter-attacks against Spanish forces, and the duke was recalled to Spain in 1573. Spanish troops, however, were no longer getting paid regularly by the crown and revolted, sacking several Dutch cities that had been loyal to Spain, including Brussels, Ghent, and especially Antwerp. These attacks were described as the “Spanish fury” by the Dutch, and they not only permanently undermined the economy of the cities that were sacked, they lent enormous fuel to the Dutch Revolt itself.

In 1581 the northern provinces declared their independence from Spain. In 1588 they organized as a republic led by wealthy merchants and nobles. Flooded with Calvinist refugees from the south, the Dutch Republic became staunchly Protestant and a strong ally of Anglican England. Spain, in turn, maintained an ongoing and enormously costly military campaign against the Republic until 1648. The supply train for Spanish armies, known as the Spanish Road, stretched all the way from Spain across west-central Europe, crossing over both Habsburg territories and those controlled by other princes. It was hugely costly; despite the enormous ongoing shipments of bullion from the New World, the Spanish monarchy was wracked by debts, many of which were due to the Dutch conflict.

England

Even as Spain found itself mired in an ongoing and costly conflict in the Netherlands, hostility developed between Spain and England. Philip married the English queen Mary Tudor in part to try to bring England back to Catholicism after Mary’s father Henry VIII had broken with the Roman Church and created the Church of England. Mary and Philip persecuted Anglicans, but Mary died after only five years (r. 1553 – 1558) without an heir. Her sister, Elizabeth, refused Philip’s proposal of marriage and rallied to the Anglican cause. As hostility between England and Spain grew, Elizabeth’s government sponsored privateers – pirates working for the English crown – led by a skillful and ruthless captain named Sir Francis Drake. These privateers began a campaign of raids against Spanish possessions in the New World and even against Spanish ports, culminating in the sinking of an anchored Spanish fleet in Cadiz in 1587. Simultaneously, the English supported the Dutch Protestant rebels who were engaged in the growing war against Spain. Infuriated, Philip planned a huge invasion of England.

This conflict reached a head in 1588. Philip spent years building up an enormous fleet known as the Spanish Armada of 132 warships, equipped not only with cannons but designed to carry thousands of soldiers to invade England. It sailed in 1588, but was resoundingly defeated by a smaller English fleet in a sea battle in the English Channel. The English ships were smaller and more maneuverable, their cannons were faster and easier to reload, and English captains knew how to navigate in the fickle winds of the Channel more easily than did their Spanish counterparts, all of which spelled disaster for the Spanish fleet. The Armada was forced to limp around England, Scotland, and Ireland trying to get back to Spain, finally returning having lost half of its ships and thousands of men. The debacle conclusively ended Spain’s attempt to invade England and eliminated the threat to the Anglican church.

The end result of the foreign wars that Spain waged in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries was simple: bankruptcy. Despite the enormous wealth that flowed in from the Americas, Spain went from being the single greatest power in Europe as of about 1550 to a second-tier power by 1700. Never again would Spain play a dominant role in European politics, although it remained in possession of an enormous overseas empire until the early nineteenth century.

The Thirty Years’ War

The most devastating religious conflict in European history happened in the middle of the Holy Roman Empire. It ultimately dragged on for decades and saw the reduction of the population in the German Lands of between 20 – 40%. That conflict, the Thirty Years’ War, saw the most horrific acts of violence, the greatest loss of life, and the greatest suffering among both soldiers and civilians of any of the religious wars of the period.

Leading up to the outbreak of war, there was an uneasy truce in the Holy Roman Empire between the Catholic emperor, who had limited power outside of his own ancestral (Habsburg) lands, and the numerous Protestant princes in their respective, mostly northern, territories. As of 1618, that compromise had held since the middle of the sixteenth century and seemed relatively stable, despite the religiously-fueled wars across the borders in France and the Netherlands.

The compromise fell apart because of a specific incident, the attempted murder of two Catholic imperial officials by Protestant nobles in Prague, when the emperor Ferdinand II attempted to crack down on Protestants in Bohemia (corresponding to the present-day Czech Republic). Ferdinand sent officials to Prague to demand that Bohemia as a whole renounce Protestantism and convert to Catholicism. The Bohemian Diet, the local parliament of nobles, refused and threw the two officials out of the window of the building in which they were meeting; that event came to be known as the Defenestration of Prague (“defenestration” literally means “un-windowing”).

The Diet renounced its allegiance to the emperor and pledged to support a Protestant prince instead. A flurry of attacks and counter-attacks ensued, ultimately pitting the Catholic Habsburgs against the German Protestant princes and, soon, their allied Danish king. The Habsburgs led a Catholic League, supported by powerful Catholic princes, while Frederick of the Palatinate, a German Calvinist prince, led the Protestant League against the forces of the emperor.

From 1620 – 1629, Catholic forces won a series of major victories against the Protestants. Bohemia itself was conquered by Catholic forces and over 100,000 Protestants fled; during the course of the war Bohemia lost 50% of its population. Catholic armies were particularly savage in the conflict, living off the land and slaughtering those who opposed them. The Danish king, Christian IV, entered the war in 1625 to bolster the Protestant cause, but his armies were crushed and Denmark was briefly occupied by the Catholic forces. This period of Catholic triumph saw the Emperor Ferdinand II issue an Edict of Restitution in 1629 that demanded the return of all Church lands seized since the Reformation – this was hugely disruptive, as those lands had been in the hands of different states for over 80 years at that point!

In 1630, the Swedish king, Gustavus Adolphus, received financial backing from the French to oppose the Habsburgs and their forces. Under the leadership of its savvy royal minister, Cardinal Richelieu, France worked to hold its Habsburg rivals in check despite the shared Catholicism of the French and Habsburg states. Adolphus invaded northern Germany in 1630, then won a major victory against the Catholic forces in 1631. He went on to lead a huge Protestant army through the Empire, reversing Catholic gains everywhere and exacting the same kind of brutal treatment against Catholics as had been inflicted on Protestants. In 1632, Adolphus died in battle and the military leader of the Catholics, a nobleman named Wallenstein, was assassinated, leaving the war in an ongoing, bloody stalemate.

In 1635 the French entered the war on the Protestant side. At this point, the war shifted in focus from a religious conflict to a dynastic struggle between the two greatest royal houses of Europe: the Bourbons of France and the Habsburgs of Austria. It also extended well beyond Germany: follow-up wars were fought between France and Spain even after the 30 Years’ War itself ended in 1648, and Spain provided both troops and financial support to the Habsburg forces in Germany as well.

For the next thirteen years, from the French intervention in 1635 until the war finally ended in 1648, armies battled their way across the Empire, funded by the various elite states and families of Europe but exacting a terrible toll on the German lands and people. From 1618 – 1648, the population of the Empire dropped by 8,000,000. Whole regions were depopulated and massive tracts of farmland were rendered barren; it took until close to 1700 for the Empire to begin to recover economically. In 1648, exhausted and deeply in debt, both sides finally met to negotiate a peace. The result was the Treaty of Westphalia, which was negotiated by a series of messages sent back and forth between the two sides, since the delegations refused to be in the same town.

The end result was that the already-weak centralized power of the Holy Roman Empire was further reduced, with the constituent states now enjoying almost total autonomy. In terms of the religious map of the Empire, there was one major change, however: despite the fact that the Catholic side had not “won” the war per se, Catholicism itself did benefit from the early success of the Habsburgs. Whereas roughly half of Western and Central Europe was Protestant in 1590, only one-fifth of it was in 1690; that was in large part because few people remained Protestants in Habsburg lands after the war.

The “winners” of the war were really the relatively centralized kingdoms of France and Sweden, with Austria’s status as the most powerful individual German state also confirmed. The big loser was Spain: having paid for many of the Catholic armies for thirty years, it was essentially bankrupt, and its monarchy could not reorganize in a more efficient manner as did its French rivals. Likewise, Spain missed out on the subsequent economic expansion of Western Europe; the war had undermined the economy of Central Europe, and the center of economic dynamism thus shifted to the Atlantic seaboard, especially France, England, and the Netherlands. There, a mercantile middle class became more important than ever, while Spain remained tied to its older agricultural and bullion-based economic system.

If the war had a positive effect, it was that it spelled the end of large-scale religious conflict in Europe. There would be harsh, and official, intolerance well into the nineteenth century, but even pious monarchs were now very hesitant to initiate or participate in full-scale war in the name of religious belief. Instead, there was a kind of reluctant, pragmatic tolerance that took root across all of Europe – the same kind of tolerance that had emerged in France half a century earlier at the conclusion of the French Wars of Religion.

Perhaps the most important change that took place in the aftermath of the wars was that European elites came to focus as much on the way wars were fought as the reasons for war. The conduct of rapacious soldiers had been so atrocious in the wars, especially in the Holy Roman Empire, that many states went about the long, difficult process of creating professional standing armies that reported to noble officers, rather than simply hiring mercenaries and letting them run amok.

Conclusion

Obviously, neither Catholics nor Protestants “won” the wars of religion that wracked Europe from roughly 1550 – 1650. Instead, millions died, intolerance remained the rule, and the major states of Europe emerged more focused than ever on centralization and military power. If there was a silver lining, it was that rulers did their best to clamp down on explosions of religiously-inspired violence in the future, in the name of maintaining order and control. Those concepts – order and control – would go on to inspire the development of a new kind of political system in which kings would claim almost total authority: absolutism.

Image Citations (Wikimedia Commons):

Little Ice Age – Robert A. Rohde

St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre – Public Domain

The Spanish Fury – Public Domain

Marauding Soldiers – Public Domain