Considering that he would go on to become one of the most significant French rulers of all time, there is considerable irony in the fact that Napoleon Bonaparte was not born in France itself, but on the island of Corsica in the Mediterranean. A generation earlier, Corsica had been won by France as a prize in one of its many wars, and Napoleon was thus born a French citizen. His family was not rich, but did have a legitimate noble title that was recognized by the French state, meaning Napoleon was eligible to join the ranks of noble-held monopolies like the officer corps of the French army. Thus, as a young man, his parents sent him to France to train as an artillery officer. There, he endured harassment and hazing from the sons of “real” French nobles, who belittled his Corsican accent and treated him as a foreign interloper. Already pugnacious and incredibly stubborn, the hazing contributed to his determination to someday arrive at a position of unchallenged authority. Thanks to his relentless drive, considerable intellectual gifts, and more than a little luck, he would eventually achieve just that.

Napoleon was a great contrast. On the one hand, he was a man of the French Revolution. He had achieved fame only because of the opportunities the revolutionary armies provided; as a member of a minor Corsican noble family, he would never have risen to prominence in the pre-revolutionary era. Likewise, with his armies he “exported” the Revolution to the rest of Europe, undermining the power of the traditional nobility and instituting a law code based on the principle of legal equality. Decades later, as a prisoner in a miserable British island-prison in the South Atlantic, Napoleon would claim in his memoirs that everything he had done was in the name of France and the Revolution.

On the other hand, Napoleon was a megalomaniac who indulged his every political whim and single-mindedly pursued personal power. He appointed his family members to run newly-invented puppet states in Europe after he had conquered them. He ignored the beliefs and sentiments of the people he conquered and, arguably, of the French themselves, who remained loyal because of his victories and the stability and order he had returned to France after the tumult of the 1790s. He micro-managed the enormous empire he had created with his armies and trusted no one besides his older brother and the handful of generals who had proved themselves over years of campaigning for him. Thus, while he may have truly believed in the revolutionary principles of reason and efficiency, and cared little for outdated traditions, there was not a trace of the revolution’s democratic impulse present in his personality or in the imperial state that he created.

The Rise of Napoleon’s Empire

Napoleon had entered the army after training as an artillery officer before the revolution. He rose to prominence against the backdrop of crisis and war that affected the French Republic in the 1790s. As of 1795, political power had shifted again in the revolutionary government, this time to a five-man committee called the Directorate. The war against the foreign coalition, which had now grown to include Russia and the Ottoman Empire, ground on endlessly even as the economic situation in France itself kept getting worse.

Napoleon first came to the attention of the revolutionary government when he put down a royalist insurrection in Paris in 1795. He went on in 1796 and 1797 to lead French armies to major victories in Northern Italy against the Austrians. He also led an attack on Ottoman Turkish forces in Egypt in 1797, where he was initially victorious, only to have the French fleet sunk behind him by the British (he was later recalled to France, leaving behind most of his army in the process). Even in defeat, however, Napoleon proved brilliant at crafting a legend of his exploits, quickly becoming the most famous of France’s revolutionary generals thanks in large part to a propaganda campaign he helped finance.

In 1799, Napoleon was hand-picked to join a new three-man conspiracy that succeeded in seizing power in a coup d’etat; the new government was called the Consulate, its members “consuls” after the most powerful politicians in the ancient Roman Republic. Soon, it became apparent that Napoleon was dominating the other two members completely, and in 1802 he was declared (by his compliant government) Consul for Life, assuming total power. In 1804, as his forces pushed well beyond the French borders, he crowned himself (the first ever) emperor of France. He thought of himself as the spiritual heir to Alexander the Great and Julius Caesar, declaring that, a member of the “best race of the Caesars,” he was a founder of empires.

Even as he was cementing his hold on political power, Napoleon was leading the French armies to victory against the foreign coalition. He continued the existing focus on total war that had begun with the levée en masse, but he enhanced it further by paying for the wars (and new troops) with loot from his successful conquests. He ended up controlling a million soldiers by 1812, the largest armed force ever seen. From 1799 to 1802, he defeated Austrian and British forces and secured a peace treaty from both powers, one that lasted long enough for him to organize a new grand strategy to conquer not only all of continental Europe, but (he hoped), Britain as well. That treaty held until late 1805, when a new coalition of Britain, Austria, and Russia formed to oppose him.

His one major defeat during this early period was when he lost the ability to threaten Britain itself: in October of 1805, at the Battle of Trafalgar, a British fleet destroyed a larger French and allied Spanish one. The British victory was so decisive that Napoleon was forced to abandon his hope of invading Britain and had to try to indirectly weaken it instead. Even the fact that the planned invasion never came to pass did not slow his momentum, however, since the enormous army of seasoned troops he assembled for it was available to carry out conquests of states closer to home in Central Europe.

Thus, despite the setback at Trafalgar, the years of 1805 and 1806 saw stunning victories for Napoleon. In a series of major battles in 1805, Napoleon defeated first Austria and then Russia. The Austrians were forced to sign a treaty and Vienna itself was occupied by French forces for a short while, while the Russian Tsar Alexander I worked on raising a new army. The last major continental power, Prussia, went to war in 1806, but its army was no match for Napoleon, who defeated the Prussians at the Battle of Jena and then occupied Berlin. Fully 96% of the over 170,000 soldiers in the Prussian army were lost, the vast majority (about 140,000) taken prisoner by the French. In 1806, following his victories over the Austrians and Prussians, Napoleon formally dissolved the (almost exactly 1,000-years-old) Holy Roman Empire, replacing much of its territory with a newly-invented puppet state he called the Confederation of the Rhine.

After another (less successful) battle with the Russians, Napoleon negotiated an alliance with Tsar Alexander in 1807. He now controlled Europe from France to Poland, though the powerful British navy continued to dominate the seas. His empire stretched from Belgium and Holland in the north to Rome in the south, covering nearly half a million square miles and boasting a population of 44 million. In some places Napoleon simply expanded French borders and ruled directly, while in others he set up puppet states that ultimately answered to him (he generally appointed his family members as the puppet rulers). Despite setbacks discussed below, Napoleon’s forces continued to dominate continental Europe through 1813; attempts by the Prussians and, to a lesser extent, Austrians to regain the initiative always failed thanks to French military dominance.

Military Strategy

Napoleon liked to think that he was a genius in everything. Where he was actually a genius was in his powers of memory, his tireless focus, and his mastery of military logistics: the movement of troops and supplies in war. He memorized things like the movement speed of his armies, the amount of and type of supplies needed by his forces, the rate at which they would lose men to injury, desertion, and disease, and how much ammunition they needed to have on hand. He was so skilled at map-reading that he could coordinate multiple army corps to march separately, miles apart, and then converge at a key moment to catch his enemies by surprise. He was indifferent to luxury and worked relentlessly, often sleeping only four or five hours a night, and his intellectual gifts (astonishing powers of memory foremost among them) were such that he was capable of effectively micro-managing his entire empire through written directives to underlings.

Unlike past revolutionary leaders, Napoleon faced no dissent from within his government or his forces, especially the army. Simply put, Napoleon was always able to rely on the loyalty of his troops. He took his first step toward independent authority in the spring of 1796, when he announced that his army would be paid in silver rather than the paper money issued by the French Republic that had lost almost all of its value. Napoleon led his men personally in most of the most important battles, and because he lived like a soldier like them, most of his men came to adore him. His victories kept morale high both among his troops and among the French populace, as did the constant stream of pro-Napoleonic propaganda that he promoted through imperial censorship.

Napoleon’s military record matched his ambition: he fought sixty battles in the two decades he was in power, winning all but eight (the ones he lost were mostly toward the end of his reign). His victories were not just because of his own command of battlefield tactics, but because of the changes introduced by the French Revolution earlier. The elimination of noble privilege enabled the French government to impose conscription and to increase the size and flexibility of its armies. It also turned the officer corps into a true meritocracy: now, a capable soldier could rise to command regardless of his social background. Mass conscription allowed the French to develop permanent divisions and corps, each combining infantry, cavalry, artillery, and support services. On campaign these large units of ten to twenty thousand men usually moved on separate roads, each responsible for extracting supplies from its own area, but capable of mutual support. This kind of organization multiplied Napoleon’s operational choices, facilitating the strategies of dispersal and concentration that bewildered his opponents.

In some ways, however, his strengths came with related weaknesses. In hindsight, it seems clear that his greatest problem was that he could never stop: he always seemed to need one more victory. While supremely arrogant, he was also self-aware and savvy enough to recognize that his rule depended on continued conquests. For the first several years of his rule, Napoleon appeared to his subjects as a reformer and a leader who, while protecting France’s borders, had ended the war with the other European powers and imposed peace settlements with the Austrians and the British which were favorable to France. By 1805, however, it was clear to just about everyone that he intended to create a huge empire far beyond the original borders of France.

Civil Life

Napoleon was not just a brilliant general, he was also a serious politician with a keen mind for how the government had to be reformed for greater efficiency. He addressed the chronic problem of inflation by improving tax collection and public auditing, creating the Bank of France in 1800, and substituting silver and gold for the almost worthless paper notes. He introduced a new Civil Code of 1804 (as usual, named after himself as the Code Napoleon), which preserved the legal egalitarian principles of 1789.

Despite the rapacity of the initial invasions, French domination brought certain beneficial reforms to the puppet states created by France, all of them products of the French Revolution’s innovations a decade earlier: single customs areas, unified systems of weights and measures, written constitutions, equality before the law, the abolition of archaic noble privileges, secularization of church property, the abolition of serfdom, and religious toleration. At least for the early years of the Napoleonic empire, many conquered peoples – most obviously commoners – experienced French conquest as (at least in part) a liberation.

In education, his most noteworthy invention was the lycée, a secondary school for the training of an elite of leaders and administrators, with a secular curriculum and scholarships for the sons of officers and civil servants and the most gifted pupils of ordinary secondary schools. A Concordat (agreement) with the Pope in 1801 restored the position of the Catholic Church in France, though it did not return Church property, nor did it abandon the principle of toleration for religious minorities. The key revolutionary principle that Napoleon imposed was efficiency – he wanted a well-managed, efficient empire because he recognized that efficiency translated to power. Even his own support for religious freedom was born out of that impulse: he did not care what religion his subjects professed so long as they worked diligently for the good of the state.

Napoleon was no freedom-lover, however. He imposed strict censorship of the press and had little time for democracy. He also took after the leading politicians in the revolutionary period by explicitly excluding women from the political community – his 1804 law code made women the legal subjects of their fathers and then their husbands, stating that a husband owed his wife protection and a wife owed her husband obedience. In other words, under the Code Napoleon, women had the same legal status as children. From all of his subjects, men and women alike, Napoleon expected the same thing demanded of women in family life: obedience.

The Fall of Napoleon’s Empire

Unable to invade Britain after the Battle of Trafalgar, Napoleon tried to economically strangle Britain with a European boycott of British goods, creating what he hoped would be a self-sustaining internal European economy: the “Continental System.” By late 1807 all continental European nations, except Denmark, Sweden, and Portugal, had closed their ports to British commerce. But far from buckling under the strain of the Continental System, Britain was getting richer, seizing the remains of the French Empire in the Caribbean and smuggling cheap but high-quality manufactured goods into Europe. Napoleon’s own quartermasters (i.e. the officers who purchased supplies) bought the French army’s uniforms from the British!

Napoleon demanded that Denmark and Portugal comply with his Continental System. Britain countered by bombarding Copenhagen and seizing the Danish fleet, an example that encouraged the Portuguese to defy Napoleon and to protect their profitable commerce with Britain. Napoleon responded with an invasion of the Iberian peninsula in 1808 (initially an ally of the Spanish monarchy, Napoleon summarily booted the king from his throne and installed his own brother Joseph as the new monarch), which in turn sparked an insurrection in deeply conservative Spain. The British sent a small but effective expeditionary force under the Duke of Wellington to support the insurrection, and Napoleon found himself tied down in a guerrilla war – the term “guerrilla,” meaning “little war,” was invented by the Spanish during the conflict.

Napoleon’s forces ended up trapped in this new kind of war, one without major battles or a clear enemy army. The financial costs of the invasion and occupation were enormous, and over the next seven years almost 200,000 French soldiers lost their lives in Spain. Even as Napoleon envisioned the further expansion of his empire, most of his best soldiers were stuck in Spain. Napoleon came to refer to the occupation as his “Spanish ulcer,” a wound in his empire that would not stop bleeding.

The problem for the French forces was that they had consistently defeated enemies who opposed them in large open battles, but that kind of battle was in short supply in Spain. Instead, the guerrillas mastered the art of what is now called “asymmetrical warfare,” in which a weaker but determined force defeats a stronger one by whittling them down over time. The French controlled the cities and most of the towns, but even a few feet beyond the outskirts of a French camp they could fall victim to a sudden ambush. French soldiers were picked off piecemeal as the years went on despite the fact that the Spanish did not field an army against them. In turn, the French massacred villagers suspected of collaborating with the guerrillas, but all the massacres did was turn more Spanish peasants against them. Napoleon poured hundreds of thousands of men into Spain in a vain attempt to turn the tide and pacify it; instead, he found his best troops caught in a war that refused to play by his rules.

Meanwhile, while the Spanish ulcer continued to fester, Napoleon faced other setbacks of his own design. In 1810, he divorced his wife Josephine (who had not produced a male heir) and married the princess of the Habsburg dynasty, Marie-Louise. This prompted suspicion, muted protest, and military desertion since it appeared to be an open betrayal of anti-monarchist revolutionary principles: instead of defying the kings of Europe, he was trying to create his own royal line by marrying into one! In the same year, Napoleon annexed the Papal States in central Italy, prompting Pope Pius VII to excommunicate him. Predictably, this alienated many of his Catholic subjects.

Russia, Elba, and Waterloo

Meanwhile, the one continental European power that was completely outside of his control was Russia. Despite the obvious problem of staging a full-scale invasion – Russia was far from France, it was absolutely enormous, and it remained militarily powerful – Napoleon concluded that it had come time to expand his empire’s borders even further. In this, he not only saw Russia as the last remaining major power on the continent that opposed him, but he hoped to regain lost inertia and popularity. His ultimate goal was to conquer not just Russia, but the European part (i.e. Greece and the Balkans) of the Ottoman Empire. He hoped to eventually control Constantinople and the Black Sea, thereby re-creating most of the ancient Roman Empire, this time under French rule. To do so, he gathered an enormous army, 600,000 strong, and in the summer of 1812 it marched for Russia.

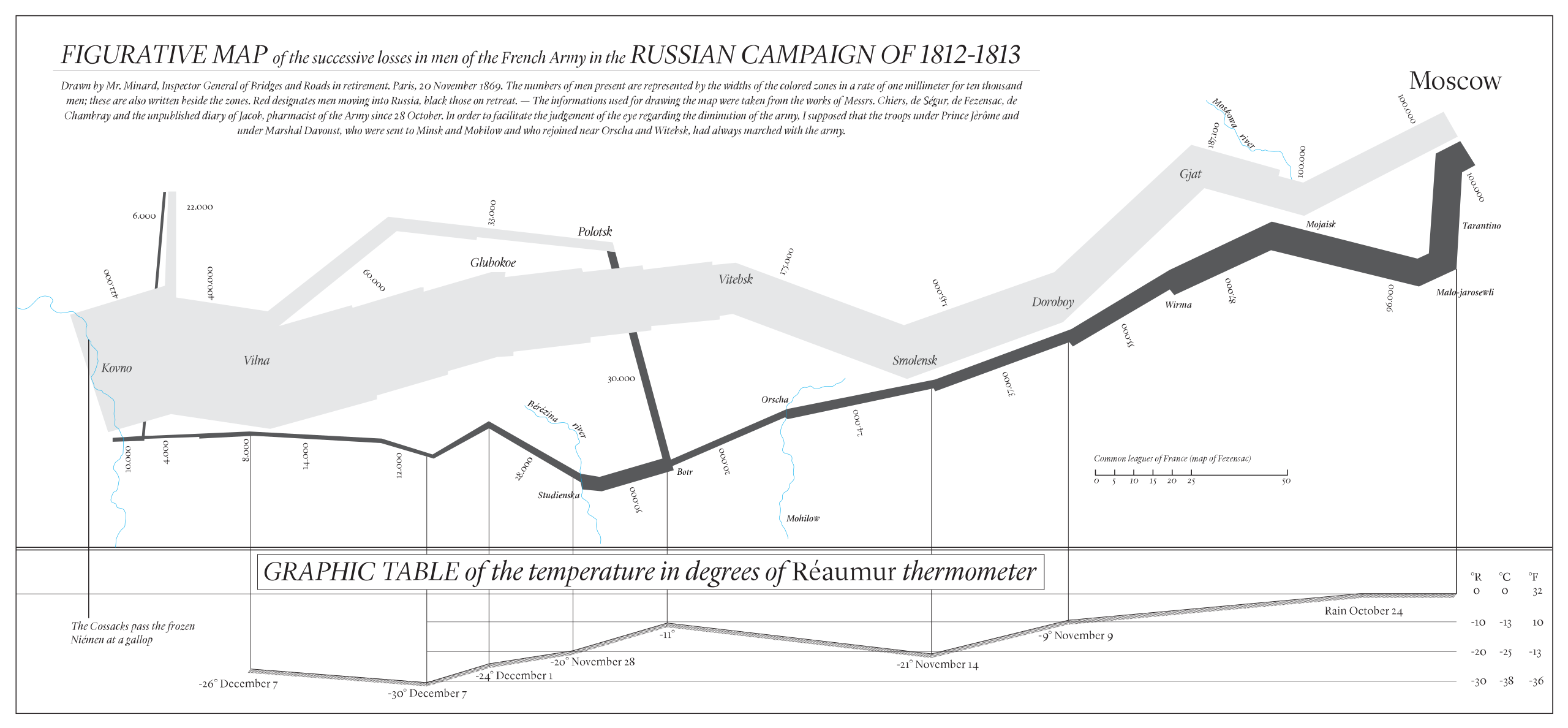

Napoleon faced problems even before the army left, however. Most of his best troops were fighting in Spain, and more than half of the “Grand Army” created to invade Russia was recruited from non-French territories, mostly in Italy and Germany. Likewise, many of the recruits were just that: new recruits with insufficient training and no military background. He chased the Russian army east, fighting two actual battles (the second of which, the Battle of Borodino in August of 1812, was extremely bloody), but never pinning the Russians down or receiving the anticipated negotiations from the Tsar for surrender. When the French arrived in Moscow in September, they found it abandoned and largely burned by the retreating Russians, who refused to engage in the “final battle” Napoleon always sought. As the first snowflakes started falling, the French held out for another month, but by October Napoleon was forced to concede that he had to turn back as supplies began running low.

The French retreat was a horrendous debacle. The Russians attacked weak points in the French line and ambushed them at river crossings, disease swept through the ranks of the malnourished French troops, and the weather got steadily worse. Tens of thousands starved outright, desertion was ubiquitous, and of the 600,000 who had set out for Russia, only 40,000 returned to France. In contrast to regular battles, in which most lost soldiers could be accounted for as either captured by the enemy or wounded, but not dead, at least 400,000 men lost their lives in the Russian campaign. In the aftermath of this colossal defeat, the anti-French coalition of Austria, Prussia, Britain, and Russia reformed.

Amazingly, Napoleon succeeded in raising still more armies, and France fought on for two more years. Increasingly, however, the French were losing, the coalition armies now trained and equipped along French lines and anticipating French strategy. In April of 1814, as coalition forces closed in, Napoleon finally abdicated. He even attempted suicide, drinking the poison he had carried for years in case of capture, but the poison was mostly inert from its age and it merely sickened him (after his recovery, his self-confidence quickly returned). Fearing that his execution would make him a martyr to the French, the coalition’s leadership opted to exile him instead, and he was sent to a manor on the small Mediterranean island of Elba, near his native Corsica.

He stayed less than a year. In March of 1815, bored and restless, Napoleon escaped and returned to France. The anti-Napoleonic coalition had restored the Bourbons to the throne in the person of the unpopular Louis XVIII, younger brother of the executed Louis XVI, and when a French force sent to capture Napoleon instead defected to him, the coalition realized that they had not really won. Napoleon managed to scrape together one more army, but was finally defeated by a coalition force of British and Prussian soldiers in June of 1815 at the Battle of Waterloo. Napoleon was imprisoned on the cold, miserable island of Saint Helena in the South Atlantic, where he finally died in 1821 after composing his memoirs.

The Aftermath

What were the effects of Napoleon’s reign? First, despite the manifest abuses of occupied territories, the Napoleonic army still brought with it significant reform. It brought a taste for a more egalitarian social system with it, a law code based on rationality instead of tradition, and a major weakening of the nobility. It also directly inspired a growing sense of nationalism, especially since the Napoleonic Empire was so clearly French despite its pretensions to universalism. Napoleon’s tendency to loot occupied territories to enrich the French led many of his subjects to recognize the hypocrisy of his “egalitarian” empire, and in the absence of their old kings they began to think of themselves as Germans and Italians and Spaniards rather than just subjects to a king.

The myth of Napoleon was significant as well – he became the great romantic hero, despite his own decidedly unromantic personality, thought of as a modern Julius Caesar or Alexander the Great (just as he had hoped). He gave France its greatest hour of dominance in European history, and for more than fifty years the rest of Europe lived in fear of another French invasion. This was the context that the kingdoms that had allied against him were left with in 1815. At a series of meetings known as the Congress of Vienna, Britain, Russia, Prussia, and Austria gathered together in the Austrian capital of Vienna to try to rebuild the European order. What they could not do, however, was undo everything that Napoleon’s legacy completely, and so European (and soon, world) history’s course was changed by a single unique man from Corsica.

Image Citations (Creative Commons):

Napoleon on his Throne – Public Domain

Napoleonic Empire – Trajan 117

Third of May – Public Domain

Napoleon’s Retreat – Public Domain

Redrawing of Napoleon’s 1812 Russia Campaign – Inigo Lopez Vazquez